Competition for the 1970 Osaka Expo: When Canadian Identity was not a Circus Affair

The 2010 universal Shanghai exposition reminds us that such major events always make us dream, in the present as in the past, but a return on the 1970 Osaka Expo, a great Canadian competition, leaves us contemplating on some aberrations of the use of architects' talents in the arts of.... circus. Since the mid-19th century, exhibitions have however offered memorable buildings, whether they are great halls housing a number of exhibitions, from London's Crystal Palace to the Galerie des Machines in Paris, or whether they are national pavilions: the 1929 German Pavilion in Barcelona by Mies van der Rohe, the 1967 American Pavilion in Montreal by Buckminster Fuller, or the 1958 Philips thematic pavilion in Brussels, the famous “poême électronique” by Le Corbusier and Xenakis.

When it comes to national pavilions, architecture has the function not only to host an exhibition but also to represent a country in the international context. A national pavilion is also a kind of temporary embassy, thus architecture plays the role of the country's diplomatic representative abroad. On the occasion of universal exhibitions, architectural competitions can be considered as a privileged milieu for the discussion of a society's values. In this context, the mission of the jury is more difficult because the choice is not confined to matters related to innovation or architectural quality, but involves very broad socio-political issues. In such cases, albeit rare, the delicate subject of the representation of the country's image is predominant. Today, as Canada was represented by a pavilion endorsed by the Cirque du Soleil in Shanghai, relegating the role of architects to the dignified role of technical consultants, it is perhaps time to revisit a historical episode of which there are still lessons to be learned, for the winning project of Arthur Erickson was actually a success at all levels.

The site of Expo '67 in Montreal was still underway when the Canadian government decided to confirm its participation in the exhibition that was to follow, scheduled for 1970 in Osaka and the first of its kind in Asia. With the theme "Progress and Harmony for Mankind", it revealed to the world the image of a developed and forward-thinking Japan, far from the depravity and aftermath of the Second World War. Some of the countries participating in the exhibition organized national architectural competitions in order to select their own national pavilions, and this was particularly the case in the United States, Finland, Brazil and Canada.

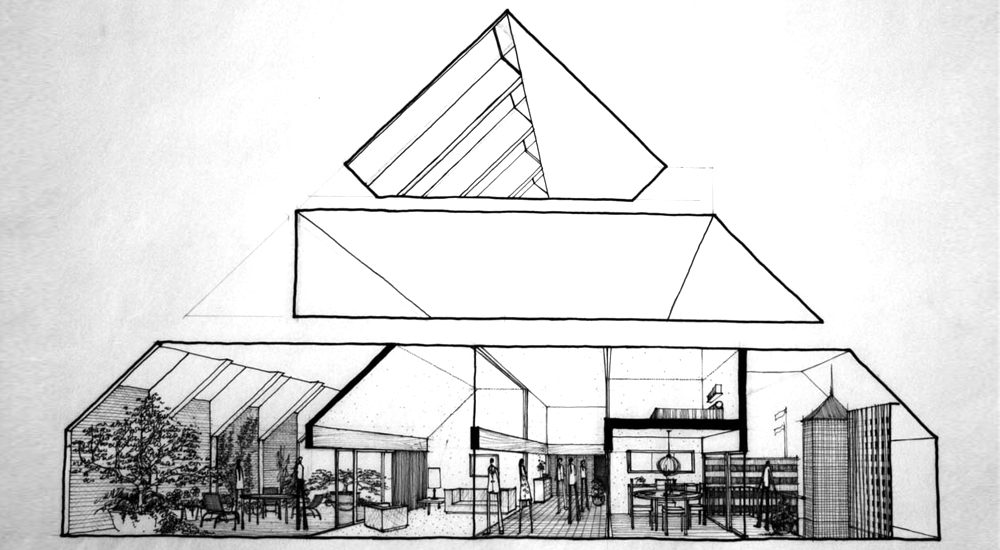

The competition for the Canadian pavilion at Osaka in 1970 brought together 208 architects, many of whom were also authors of buildings on the site of the 1967 exhibition in Montreal. The winning architects, Arthur Erickson and Geoffrey Massey, were also the designers of three buildings: the pavilion of Man in His Community, its annex, the pavilion of Man and his Health, and, lest we forget, the architects of the Canadian pavilion! With historical hindsight, we can now say that this multiple election was not the result of coincidence or manipulation but a direct consequence of the designers' particular sensitivity towards the image of a country that sought to assert its modernity. The 1970 Canadian pavilion project in Osaka evoked the grandeur and simplicity of Canadian territory, with its mountains, its vast sky, great forests and abundant water, where the entire form - very assertive and very clear – with four mirror-covered volumes, forming a truncated pyramid with a central courtyard. This project, heavy with symbolism and kaleidoscopic visual effects delighted the jury members and all the visitors to the Expo, it made the cover of almost every Japanese catalogue and magazine of the time; it was the foreign pavilion most visited and received among other prizes, the prize by the Architectural Institute of Japan and the Massey prize.

This month, the Canadian Competitions Catalogue invites you, where the coverage of major expositions is propitious, to discover not only the memorable project of the grand Canadian architect who died last year, but also the projects by Melvin Charney, Roger D 'Astous, the group Affleck, Desbarats, Dimakopoulos, Lebensold, Sise and other names, who have since become famous across Canada.

Coincidence or not, a little more than a decade after the exhibition of Osaka, Arthur Erickson developed the project for the Canadian Embassy in Washington. This reminds us that between the architecture of a universal exhibition event and that of a permanent architecture, questions of diplomatic and cultural representation arise, just as questions of creativity and imagination, but not always questions of transparency of either procedures or judgements. The enthusiasm with which the country experienced the universal expositions of Montreal in 1967 and of Vancouver in 1986 therefore merits a rediscovery of a competition that is already forty years old: given that there are always challenges to raise in architecture.

(translated by Carmela Cucuzzella)

The construction of Expo 67 in Montreal was still in progress when Canada confirmed its participation in the next exhibition, Osaka 1970, becoming the first foreign country to confirm its presence at the Japanese exhibition. It was the first of its kind in Asia and its theme was "progress and harmony for humanity", with the aim of showing the world the image of a developed and avant-garde Japan.

The context of the organization of the competition for the Canadian pavilion in Osaka coincided with the post-war economic development, the baby boom, the Quebec Quiet Revolution, the centennial of the Canadian confederation and the 1967 Montreal World's Fair. There was a certain enthusiasm for world's fairs and the role that national pavilions could play in the diplomatic and cultural representation of the country abroad. Organized by the Department of Trade and Commerce and the Canadian Government Exhibition Commission, this competition brought together 208 architects, many of whom were also designers of buildings on the site of the Montreal exhibition.

Lasting six months, and with two stages of projects, this competition raised a debate on what would be the best image that Canada should bring to the Japanese exhibition. The jury's report made it clear that the pavilion must achieve a "strong and dramatic" image and that it must stand out from the other pavilions at the exhibition. In short, an image of self-confidence. Of the six finalist projects, the jury chose that of Vancouver architects Arthur Erickson and Geoffrey Massey, arguing that this project presented the most sensitive approach to the image of Canada and made a significant connection with Japanese aesthetic sensibilities.

(CCC text)

(Unofficial automated translation)

In October 1966 Canada became the first country to accept the invitation of the Japanese Government to participate in the Japan World Exposition being held, with the sanction of the International Bureau of Exhibitions, at Osaka, Japan, from 15 March to 13 September 1970. This Exposition, the first of its kind in Asia, is expected to contribute significantly to social understanding between East and West. The objective of the Canadian participation is to leave a vivid, favourable and lasting impression of Canada and its people in the minds of the estimated 30 million who will visit Expo '70. In view of the importance of this project, the Canadian Government through the agency of the Canadian Government Exhibition Commission of the Department of Trade and Commerce and after an extensive feasibility study, decided to Sponsor an architectural design competition. Open to all members of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada resident in Canada the competition for the Canadian Pavilion at Osaka was approved by the RAIC and was conducted in accordance with RAIC Document No. 4.

In view of the limited time that was available for the competition and the incomplete information about the Master Plan for Expo '70, it was decided to hold the competition in two stages. Conceptual designs based on information available up to the end of December 1966 were requested in Stage 1. The competitors selected for Stage II were able to develop their designs, guided by a more detailed development of the Expo '70 site Master Plan and the revised theme and exhibit intent outline available in April 1967.

The program required provision of approximately 43,500 sq. ft. of varied exhibition space, 15,000 sq. ft. of service and ancillary accommodation and development of the entire site area of 103,337 sq. ft. Strict requirements with regard to the final cost of the construction of the pavillon were stipulated in the competition conditions and an independent team of quantity surveyors carried out detailed analysis of designs and cost estimates submitted by competitors in both stages of the competition.

In spite of the tight schedule and limited working time (eight weeks in Stage 1 and nine weeks in Stage II) the response from the architectural profession in Canada was most gratifying. There were in all 208 entries. A conservative estimate of the effort expended by Canadian architects has been evaluated at approximately $ 1,050,000.

The submissions showed great variety and imagination, a high calibre of architectural thought and an impressive level of professional competence. The Jury was faced with the difficult task of selecting, from the entries in Stage 1 and the six finalists in Stage II design incorporating in equal measure architectural qualities and exhibit potential.

Warm congratulations are due to Erickson/Massey, whose brilliant design was unanimously selected by the Jury as winner in Stage Il. Special commendation is due to each of the remaining five finalists for the excellence, competence and distinction achieved in their designs. In addition to the six finalists, each of whom received a premium of $4,500, the Jury felt that, from Stage 1, six additional designs deserved to be singled out for Honorable Mention and 31 designated as Designs of Merit. The illustrations in this report are shown in alphabetical order within each category as the Jury assigned no particular order to the merit entries.

The Jury deeply regretted the absence of Professor Kenzo Tange of Japan who originally agreed to serve as a member of the Jury, but was prevented at the last minute from taking part in the judging through circumstances beyond his control.

In concluding this report, sincere expressions of gratitude are due to the members of the Jury who, having accepted the invitation to serve, discharged their difficult task wisely, conscientiously and impartially. Congratulations are tendered to the architectural profession across Canada for the level of professional excellence achieved in this competition; and compliments are paid to the Sponsor, represented by the Honourable Robert H. Winters, Minister of Trade and Commerce, for the decision to hold this competition and to publish, at the Jury's suggestion, this report. To the staff of the Canadian Government Exhibition Commission, who were instrumental in ensuring with quiet efficiency that the Sponsor's preparations for the competition were complete, our appreciation is expressed.

It was a great honour, privilege and pleasure to serve as Professional Advisor and to conduct this competition.

(From jury report)

(Unofficial automated translation)