OMA in Quebec: Office for MNBAQ Architecture

It is an immense sign of cultural maturity, by choosing to open the design of one of the most prestigious buildings in Quebec to international competitors, by allowing Quebec architects to measure themselves, at home, against the best teams in the world, based on a three phases process that was as balanced as it was rigorous, the Musée National des Beaux-Arts, in addition to the unanimous selection of a response to a difficult problematic, has finally assured that Quebec made it into the major league of international competitions.

A brief historical overview of the past 50 years reveals that the world of architecture has not always been so open, as we may sometimes think, in the “belle province”. In the fall of 2013, or even winter 2014, when the proposed new pavilion will have been built by the winning team comprised of a consortium including OMA, the leading Dutch agency (under the direction of Rem Koolhaas) and the leading Quebec office, Provencher Roy and Associates, architectural historians may say - and this in itself is surprising - that this is the first time in Quebec history that a foreign team will have been authorized to build here following a competition.

Let me be clear. There were many other competitions and many other foreign architects to flourish in Quebec. But by consulting the current data of the CCC, certainly always under construction, I found barely any foreign winners and never any projects built by foreigners. Careful, we are not referring to the painful episode of the Olympic stadium, by the visionary mayor and the French Mandarin, an operation that forced many people to smoke cigarettes in order to repay the propensities for the oblique because the stadium was primarily a princely order. We are also not comparing the MNBAQ competition with the extraordinary competition for Toronto City Hall in 1958, which brought together over 520 participants from around the world – a shocking figure that invalidates any possibility of a fair judgment - because this competition primarily allowed Québec architects to measure themselves with their Canadian counterparts. A few major competitions were organised in the 1980s, especially for museums (National Museum of Civilization in 1980 and the Museum of Contemporary Art in 1983), but whether it involved 5 or 101 competitors, they came exclusively from Quebec. We are neither referring to competitions of ideas, which we accept to open at an international level, primarily because these refer just to ... ideas. A first breach was opened in 1990, with the Place Jacques Cartier competition, which brought together 8 international teams and was won by a promising Quebec architect, Jacques Rousseau.

The cultural competitions of the 1990s, often small scale, were systematically restricted to Quebec practitioners, but they had a very important function. The exhibition organized within the framework of a research by Professor Denis Bilodeau, for the period 1990-2005, showed the considerable impact that all these competitions of museums, libraries, cultural centers, etc., had at the time for the recognition of a territorial imaginary across Quebec. It is difficult to understand why the competition procedure continues to create distrust in the profession, when we measure their educative power over decision makers and those that provide the work, as many of them recognize a posteriori. This cultural policy was intended to stimulate Quebec architecture and it was a success.

Only at the turn of the century, exactly in 2000, Quebec architecture accepted once more to compete on an international scale, with the competition of the Grande Bibliothèque du Québec. The result was relatively conclusive, the collaboration between the Canadian and Quebec winners, was rough at times, may we say, and the jury's verdict gave rise to much speculation, fuelled by the fact that the government has not yet released the jury report: more than 10 years after the verdict. If this competition was not the most transparent, the building continues to demonstrate its relevance to users.

That leaves, as the only previous competition won by foreign architects, the one held for the Cultural and Administrative Complex (MSO) in 2002. Remember from the outset that the cultural program was literally phagocytised by the surface area allocated for offices, that however led to a major two stage competition, the first phase completely open, gathered more than a hundred projects from around the world, and where the second phase positioned 5 teams, with at least two comprised entirely of Quebec practitioners, on an equal footing, and the winner of which was both Dutch and Quebecois (consortium of De Architekten, Aedifica and TPL and associates). A change of government precipitated the cancellation of the order, where this government never authorized the release of the jury report: a perfect recipe to undermine the process (presumably for the benefit of PPP), a perfect recipe to frustrate the professionals (an abortive competition is not good for anyone) and a perfect recipe to give free rein to the journalists always quick to reduce the complexity of an architectural project to some metaphorical caricature, as it is easy to mock the "big box" (since, may we specify that the 100 000 m2 of the brief was difficult to contain in a small box).

It is therefore slightly easier to understand the enthusiasm of the architects (young and less young) conscious of the international recognition of their discipline, concerned with quality and excellence, but equally, the surprise of critics and historians who today realize that with the result announced by the management of the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec, and if all proceeds as planned, the shock waves and influence of the outcome should have exemplary effects. History will tell if this is really the first competition in which the search for the best project took precedence over other considerations. The fact that it is a foreign team that leads the development of a national project is not at all a failure of Quebec architecture, it is all the more commendable in its quest for excellence and therefore it can be seen as an encouraging sign of cultural maturity.

We will take other opportunities to comment on the actual architectural projects presented, because it is important here to highlight one final aspect of this great event. It is essentially the first time that a competition organizer for a public building ensures the dissemination of ALL projects IMMEDIATELY after the announcement of the result, as an obvious concern for transparency. Hoping that the Canadian Competitions Catalogue serves as a platform for dissemination to the widest audience, both here and internationally, the management of the Musée National des Beaux-Arts recognizes the importance of the mission for the diffusion of contemporary architecture that the researchers of the L.E.A.P were given, which confirms the status of this competition as an exemplary event.

(translated by Carmela Cucuzzella)

The Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec opened its doors in 1933. Its most recent expansion dates back to 1988-91. The primary goal of that expansion was to integrate a heritage building, the former Quebec City prison, built in 1861 and neglected since the 1970s. The 1988-91 expansion also made possible a temporary improvement in the level of service with the addition of new spaces. The placing of an entrance lobby between the 1933 structure and the 1861 prison created an impression of a museum closed in upon itself in the midst of the Plains of Abraham and imparted a vision of an institution that had, in a sense, ceased growing. In fact, together the buildings in the complex inaugurated in 1991 occupied practically all the space owned by the institution upon which it might build.

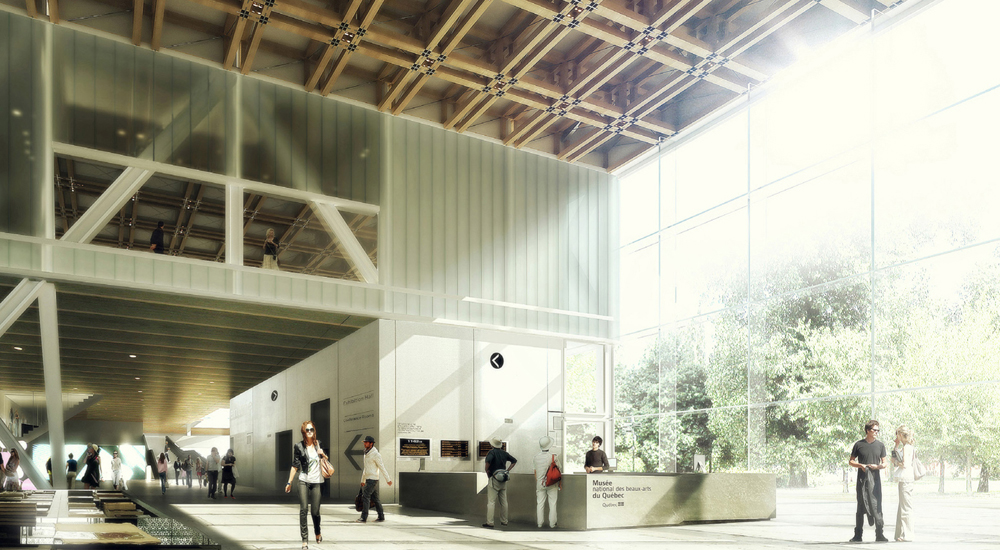

In this context, the project of a new pavilion for the Museum is a decisive architectural gesture by virtue of both its intrinsic novelty and opening onto the urban space of the Grande Allée and its underground connection with the initial complex, in a desire to respect the Museum's natural environment.

The present project thus marks a change of course, because it is part of an entirely new perspective of openness. It is a major step, but it is important to understand what it is and is not in order to avoid any ambiguity. It is thus not a question of opening the door to a broader or more ambitious gesture than that of building a new pavilion. Thirty or forty years from now new expansion projects may be contemplated, whether by annexing the present-day Saint Dominique church (which would be re-designated) or by building a major addition between the Museum's present Gérard Morisset and Charles Baillairgé pavilions, where the present-day entrance pavilion is located.

Beyond this long-term vision, for the moment the Museum is planning a significant architectural gesture adapted to its priorities and in keeping with its budgetary resources. This building will be located on an open site on the Grande Allée, which the Museum already owns. Incidentally, this is the only site upon which a new pavilion can be built, given that the National Battlefields Commission (NBC) is refractory to any cession, no matter how small, on the Plains of Abraham. It is open, however, to the creation of underground spaces linking the new pavilion to the present-day Museum which do not alter the existing green spaces.

The project of a new pavilion for the MNBAQ raises particular challenges, because of both its complexity and its modest scale. From the outset, the Museum is seeking an unhesitatingly contemporary gesture beyond the “heritage” nature of its surroundings.

When the exercise is complete, the Museum's architecture will stand out for the way it belongs to the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, reflecting the make-up of its collections, which, we should recall, are both historical and contemporary. The same is true of Quebec City: a living reality with its own historical strata but also wishing to be anchored in the present with a vision of the future. We should add to this description the marked urban aspect of the new pavilion, with its opening onto the Grande Allée corresponding to our quest for a new institutional image.

It will thus be understood that the architectural project sought will be closer to creating a new work than to mimicking our existing buildings. The Museum is in search of a strong conception, a true architectural project, and not simply a construction project whose result is the availability of new spaces. There is real complexity, and an even greater challenge, in the need for the project to reconcile a creative act with an imperative respect for a budget that is, for all that, modest.

Finally, the institution seeks to create an exemplary project by means of a transparent exercise with a pedagogical aspect capable of reaching the general public while promoting full use of the new MNBAQ by the population as a whole.

This new pavilion should project the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec into the future by providing cutting-edge technical performance within a sustainable development approach. LEED Canada certification is sought.

(From competition documentation)