Canadian landscape: A deferred invention

We often say that Canadians, proud of their great spaces, are particularly sensitive to the quality of the landscape. Beyond clichés, occurrences are few and far between. Out of a total of nearly 180 inventoried competitions since 1945, there are less than ten devoted to landscape. However, there is not a lack of talented landscape architects. Why do we defer the invention of tomorrow's landscape?

In this belated September 2006 update, we present projects submitted for a competition in 2005 organized in Halifax. Twenty-six competitors presented a project during this competition's first stage, of which five were selected to further develop their ideas during a second stage (four Canadian teams and one Japanese team). It is important to mention that the jury, relying very (or overly) wisely on compromise, proposed that the services of two winning teams be used: the master plan prepared by NIP Paysages and the strategic management of Ekistics Planning and Design. Is it always necessary to choose the best of both worlds? The realization of this project will only tell, as organizers requested that the two teams work together: dissociating brains from brawn.

We equally invite internauts to discover, or rediscover, the many projects from different countries, that were submitted during the two competitions organized for the re-planning of the Montmorency Falls sector in Québec City in 2004. Entitled, "Perspective Littoral", this competition, that had professionals and students working in parallel, was astonishingly fruitful, and revealed an international interest in powerful sites. The unstructured environment of Montmorency Falls is indeed a blemish to the landscape: it is enlightening to compare Canadian and foreign attitudes towards comprehending territorial and cultural issues of such valuable (world?) heritage.

Please note that the Laboratoire d'étude de l'architecture potentielle has yet had the opportunity to document other competitions dealing with parks and gardens that were organized in Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia. We ask that all landscape architects interested in contributing to this archiving and communication endeavour, contact our research team (leap-lab@umontreal.ca).

Leaving the question of the deferral of landscape invention in Canada unresolved, we end by mentioning, once again, the beautiful project by Montreal architects at Atelier in situ for the visitor welcoming pavilions of the Jardins de Métis. The organization of this notable competition, having generated a form of "invention" itself in regards to its conceptual approach, invited all competitors to work on site, within the garden itself, during the summer of 1999. At the threshold of the 20th century, the "call of the landscape" could not have been clearer: "Architects, to the fields!"

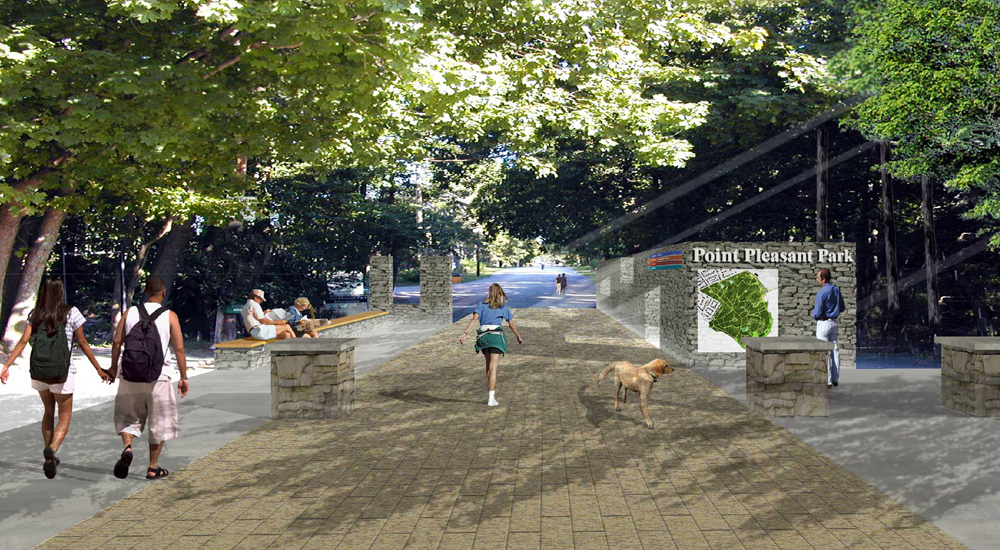

Point Pleasant Park lies on a rocky promontory jutting into the Atlantic Ocean at the eastern end of the Halifax peninsula, in Nova Scotia, Canada. This park has been a place of recreation for the citizens of Halifax since the city's founding in 1749. It is open year round permitting a variety of use such as walking, picnicking, skiing, cycling and dog walking.

In late September 2003, Hurricane Juan hit the Nova Scotia coast not far from Point Pleasant Park. It caused millions of dollars of damages in Halifax, and destroyed more than 75 000 trees in the park.

Point Pleasant Park was closed to the public for nine months in order to clean up the debris. With almost 85 per cent of the trees removed and its shoreline damaged, the park needed to be completely renewed.

In response to the contest, 26 projects were submitted in the first stage, and 5 were selected for the second stage (4 Canadian teams and a Japanese team). The jury thought wise to compromise and proposed two prize winners, choosing the best of two worlds and hoping that NIP Landscape with its master plan and Ekistics Planning and Design with their strategic management qualities would combine their efforts for the best results.

Principles and goals:

The theme, Regenerate Restore Renew helped competitors define a sustainable project that restores the feeling of the original landscape of the park previous to Hurricane Juan.

The participants had to submit a phased approach for the master plan implementation incorporating specific renewal projects within the following time frames: 1 year, 2 to 5 years, 6 to 20 years, and 21 to 50 years.

The design also had to reflect the relationship between the citizens and their park, defining it once more as a place of regeneration, exercising, picnicking by the sea, meeting place and much more.

(CCC text)